Have You Got What It Takes To Be A Humanitarian Worker?

A CTG team helps clear mines in the Congo

When my Skype rang, I saw that it was Doctor George calling me. He’s a capable emergency physician, and we at CTG were excited to have found someone so willing to go and work in our field hospital in Basra, between Kuwait and Iran. “James, can you hear me?” Skype was sketchy as usual, but I could just about hear him. “I’m leaving tomorrow,” he said. “What’s that? Doctor George, did you say you’re leaving?” Yes, he replied. I didn’t understand, as he had only just arrived. What could be wrong? “It’s too hot and sandy,” he said. I was speechless. What did Doctor George expect? he was going to work in a remote field hospital in Basra!

A consultant practises a medical emergency scenario

The point of this light-hearted anecdote is twofold: firstly the individual had not prepared himself for what was ahead of him and secondly we had not done our due diligence to make sure he was cut out for the job. Working in post-conflict environments is not everyone’s cup of tea, that is for sure, nor does it need to be. It is tough, often monotonous, sometimes dangerous, occasionally scary, always frustrating and usually quite alien. On the flip side, it can be extremely rewarding with rich human encounters, humbling experiences, plenty of laughter and great friendships that last forever. So what does it take to work as a humanitarian in extreme contexts? Well, there is certainly no one-size-fits-all response to that question and it is almost easier to describe what doesn’t work than what works but I’ll try a bit of both.

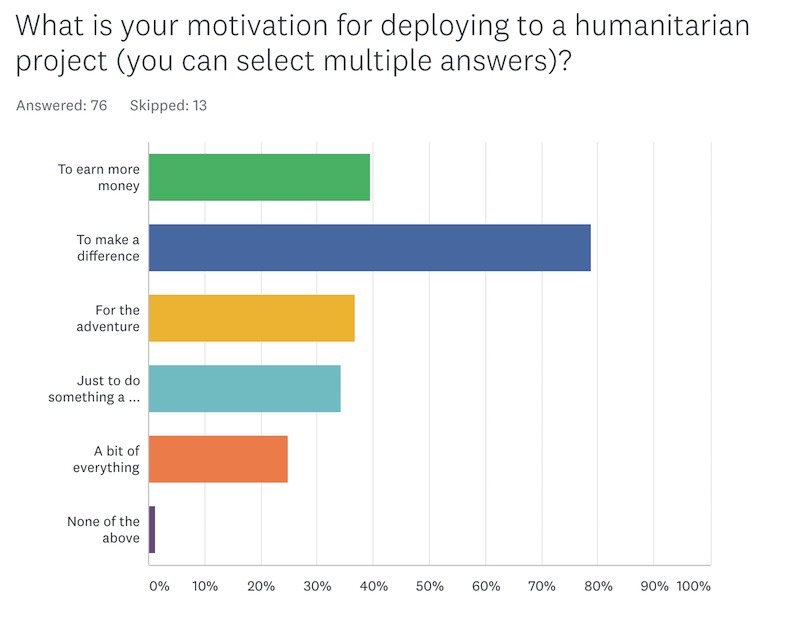

In a recent CTG survey aimed at prospective applicants for humanitarian work, 79 percent of respondents said their primary motivation is to make a difference. Nearly 67 percent said they have experienced living in a developing country.

People who have traveled a lot, speak multiple languages and are comfortable with, and indeed seek out, cross-cultural experiences usually do well in humanitarian aid work. In the 1980s humanitarian aid was something that was “given out” as charity (it still is to a large extent but I’ll save that hot topic for a rainy day) however, today local engagement and local solutions to local problems is far more prevalent.

So people with a natural curiosity, an openness of mind, the humility not to assume that the “aid givers” have the answers and the simple gift of striking up conversation with absolutely anyone are all qualities that stand you in good stead as a humanitarian worker.

Not needing much sleep is also pretty handy! I say that slightly tongue in cheek, but working on humanitarian projects is extremely intense in every way. People tend to work all of the time (there isn’t much else to do, especially if the security risks are high and movement is restricted) although in some cases the social life can be pretty active too. The work itself can be draining both from a human perspective and the general stress of trying to get things done where nothing works as it does back home. I would go a step further to state that people who are able to remain grounded and balanced are usually successful over the long-term and that does include looking after your own health and wellbeing (physical and mental).

My colleague Lucy once dragged me off one morning in Mogadishu at 5am to a sunrise yoga session on the beach, just down from the Ugandan soldiers’ hut guarding the coast line from the threat of Al Shabab. I’m not a big yoga fan, but it was incredibly peaceful and I was very grateful to the aid worker who gave up her early mornings to take these sessions which set us up for the day ahead.

Exercise can form a big part of your social life when you’re placed in remote locations

That leads me onto the support network. People who succeed in the “field” usually have a solid grounding at home. Sadly, my personal observation is that many people attracted to remote field work are often running away from something and don’t always have the safety net of a solid base to return to. We all get asked the question “when are you going to get a real job” and whilst it’s a little frustrating (hey, we’re saving the world, aren’t we?) it’s understandable because what we do as humanitarians isn’t exactly normal but having the basics of a support network is a key success factor.

A camp in Mogadishu, Somalia, teems with day-to-day activity

I can usually tell if someone is going to be a success in the field before they’ve even arrived. Our recruiters work day and night to source candidates from all over the world and sometimes, believe it or not, candidates can be unbelievably pushy and even rude and yet somehow they end up getting selected for the position (our clients have final decision making on the right fit). Another indicator is usually discovered waiting in the long and often sweaty queues at immigration on arrival. One time I was queuing for my arrival visa in Somalia when a rather brash man in a suit pushed past me waving his paper work and stated shouting at the local immigration officer “I’ve got my visa you so-and-so’ … I was not only embarrassed for us “foreigners” but I also thought to myself, that guy isn’t going to last long. It seems a total platitude, but basic manners, courtesy and a healthy dose of patience are essential qualities for any humanitarian worker. Rudeness sends you right to the back of the queue, in my experience.

Enough from me, these are just my thoughts from my peripatetic lifestyle supporting the humanitarian community. We’d love to hear from you and if you think you might have what it takes to deploy to a CTG project, why not take the test? Good luck and we look forward to hearing from you.