Does paternity leave have a role to play in progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal of Gender Equality?

While progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal of Gender Equality (SDG 5) demands movement away from traditional male and female household roles, the governments that do grapple with policies to alleviate gender stereotypes are not being met halfway by their citizens.

With the number of countries that legally reinforce paternity leave doubling over the last 20 years, it’s easy to overlook the percentage of fathers that actually takes the opportunity. While at least four of every ten organisations across the globe pay more than the statutory minimum over the course of a father’s paternity leave, men and women still fail to flout the gender norms that might otherwise lead to improved labour market participation overall.

Although it’s clear that Gender Equality in the workplace cannot be achieved while early parenting is institutionally left to mothers, the proportion of men taking the opportunity to shake their stereotypes remains stubbornly low in the countries where they can.

What’s stopping fathers from staying home?

Men across the working world who reject paternity leave describe anxiety about being discriminated against professionally. Reasons for not taking time off include fear of missing out on pay rises and promotions, being marginalised, or even being mocked by colleagues. These concerns signal deeply ingrained stereotypes around gender and stock roles for parental figures around the home.

In which countries can fathers stay home?

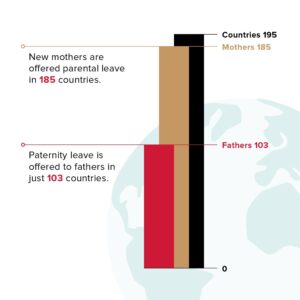

While new mothers are offered some kind of parental leave in 185 of the world’s 195 countries, paternity leave is offered to fathers in just 103. While CTG operates largely within countries that offer under a week’s paid paternity leave, conversely, some of the countries offering the most have parents accepting the opportunity the least.

While new mothers are offered some kind of parental leave in 185 of the world’s 195 countries, paternity leave is offered to fathers in just 103. While CTG operates largely within countries that offer under a week’s paid paternity leave, conversely, some of the countries offering the most have parents accepting the opportunity the least.

For example, South Korea and Japan are ahead of the curve for paternity leave by far. New fathers are entitled to up to 12 months of leave to stay at home with new-born children, though the OECD reports that only 2% of fathers accept this offer.

In 2015, the UK introduced a shared parental leave policy allowing parents to split up to 50 weeks of leave and up to 37 weeks of pay between them. However, research in 2018 revealed that of the 900,000 UK parents eligible to take advantage of the policy that year, only 1% of parents did.

Paid paternity leave is offered in countries of all economic status. While generally nations with a higher GDP provide more generously, this is not always the case and does not reflect that percentage of fathers who take what is on offer.

Interestingly, in countries with a high infant population and upper-middle average income like Brazil, or countries with a low average income like the Democratic Republic of Congo, less than 3 weeks of paid paternity leave is offered. Meanwhile, low-income Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Mongolia offer a minimum of 14 weeks paid paternity leave.

In the last 10 years, a number of African nations have introduced paid paternity leave in a movement towards family-friendly policymaking across the continent. Mauritius introduced 1 week in 2008, Rwanda introduced 4 days in 2010, and Gambia has introduced 14 days.

Is paternity leave the next step towards Gender Equality?

While the potential for paternity leave to tip the scales forward into gender parity is undeniable, changes to policy across the world have not had the desired effects just yet. It seems that the provision of paternity leave isn’t enough: to shake the stereotypes that keep fathers bound to their workplace, governments need to systematically encourage the practice.

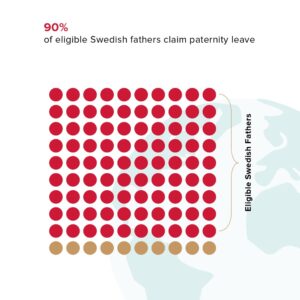

Countries like Sweden have bolstered the rates of men taking paternity leave by offering parents 480 days of paid parental leave per child – days that they are entitled to share. Each parent can transfer part of their leave to the other, but 90 days have to be reserved specifically for each parent. From 2008 until 2017, as an incentive for fathers to take more time off, families were

entitled to a monetary bonus determined by the number of days divided equally between parents.

The policy seems to be working: One study in 2019 showed that approximately 90% of eligible Swedish fathers claim paternity leave and that on average, they take 96% of the total amount of leave time allotted to them. Sweden is also a leader among advanced economies in terms of female labour market participation.

Rejection of paternity leave across the world is symptomatic of a global culture that is not yet willing to take a leap towards Gender Equality. While its trajectory is promising, governments and businesses will have to offer more, encourage more and push more in order to promote changes in attitude that can really tip the scales against discrimination in employment.

***

Ella Holliday is interning as part of the Communications team at CTG, producing research as well as materials pertaining to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. She is currently working towards a French and Spanish degree at the University of Oxford, and has been drawn to international affairs since moving to Myanmar to teach English in 2019/2020.